Above: Patriots pull down statue of George III at Bowling Green, 1776 (Howard Pyle-National Archives)

“It was a breakthrough for you…when you realized that Nelson Mandela was actually just a leftist. Then it was another huge breakthrough for you when you realized that Martin Luther King was actually just a leftist…But you think you’re done, don’t you? I want to see the expression on your face when you realize that Samuel Adams was actually just a leftist.”

- Curtis Yarvin

The above quote is the money shot in a sprawling debate between Christopher Rufo and Curtis Yarvin which took place earlier in the year, and seemed appropriate to revisit on a Fourth of July extended weekend. Rufo and Yarvin are both right-wing superstars, but they have an important divergence. Rufo is a conservative, that is, someone who strives to moderate the side-effects of social change. Yarvin is a reactionary, that is, someone who desires flat-out counter-revolution.

Yarvin is probably a fascist but that doesn’t change the fact that he’s a good writer with valuable things to say. In fact Yarvin, the supreme anti-communist, may understand Marxism better than most American socialists currently do. He seems to be worried that Rufo’s present anti-Woke campaign could accidentally revive classical Marxism by suppressing “race Marxism” and sparking revolutionary spirit in America. He may be right to worry.

Christopher Rufo has lately said that he is leading “a counter-revolution” though, and that’s probably why Yarvin is confronting him—Rufo is cutting in on his territory. As they jibe back and forth, Rufo sounds self-assured, but also reveals himself to be deeply confused. He calls himself both a “radical” and “a conservative,” something which isn’t possible unless one is also a fascist. But fascism rules under a state of emergency, and Rufo didn’t like the Covid states of emergency, and is definitely against the de facto McCarthyite state of emergency that Joe Biden has declared ever since January 6th. Rufo also says he celebrates the American “republic” above all, and that his role model as an activist is Samuel Adams.

However, Rufo then says that the founding of the US is “better described as a counter-revolution.” If the concept of a “second American revolution” is conservative enough for the Heritage Foundation, why would Rufo abjure it? I suspect Rufo is closer to grassroots politics than Heritage is, and may have a working-class constituency he has to justify things to. If he embraced a second American revolution then that revolution would have to go further toward equality than the first one did. And Yarvin’s point is that egalitarianism was at the heart of the American Revolution.

To make his case, Yarvin cites a debate between Samuel Adams and John Adams in 1790. Samuel, progenitor of the fight for independence even more than his cousin was, rejected John’s apologetics for hereditary nobility, affirmed that all men are created equal, and declared that majorities always run society better than minorities do. Sam Adams also made a case for public education that’s extremely awkward for Rufo, the homeschooling advocate:

Wise and judicious Modes of Education, patronized, and supported by communities, will draw together the Sons of the rich, and the poor, among whom it makes no distinction; it will cultivate the natural Genius, elevate the Soul, excite laudable Emulation to excel in Knowledge, Piety, and Benevolence, and finally it will reward its Patrons, and Benefactors by sheding its benign Influence on the Public Mind.

Since Rufo has expressed belief in a direct ancestry between Josef Stalin and anti-Stalinists like Herbert Marcuse, he can hardly dismiss the relationship between Samuel Adams and Marxists like Nelson Mandela, especially when so many communists have claimed Sam Adams as their ancestor over the years. The best he can do is insist that the Founding Fathers were actually counter-revolutionaries, a claim that sounds strangely…Woke.

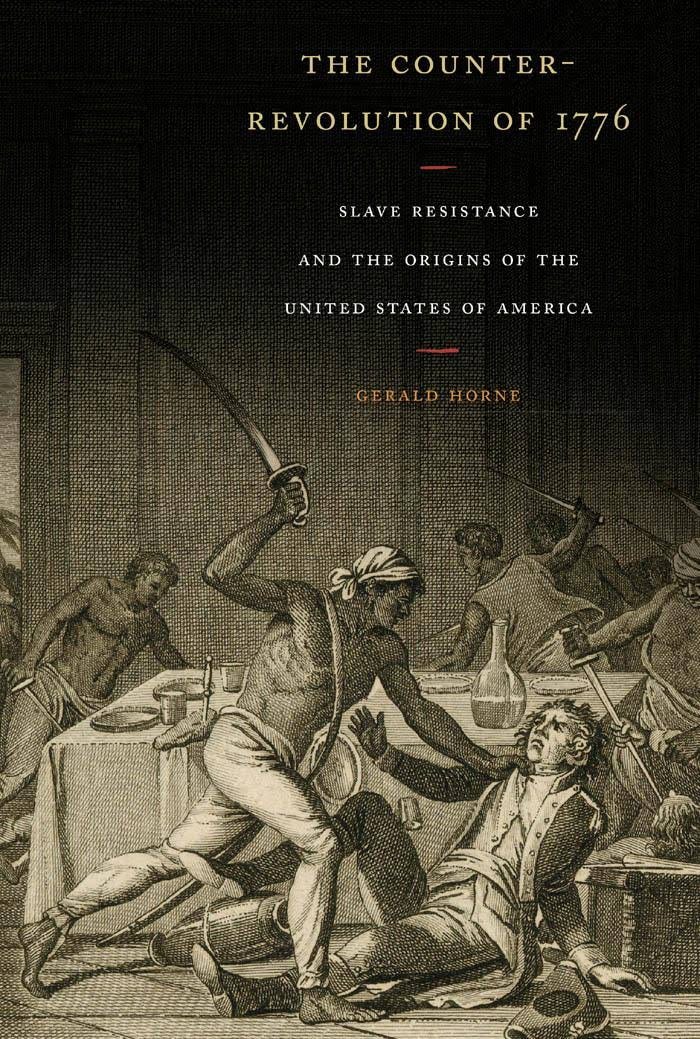

One of the hallmarks of Wokeness is The 1619 Project. This is the highly promoted New York Times series which argued that the British were briskly on their way to abolishing slavery in 1775, and the purpose of the War of Independence was mainly to preserve laws that treated black people as property. A foundational source for The 1619 Project is a book by Gerald Horne entitled The Counter-Revolution of 1776.

With The 1619 Project, the establishment promoted the idea that 1776 was a counter-revolution. It’s tragic that anyone calling themselves a populist would fall into their trap.

From Radical Reformation to Radical Enlightenment

The roots of this delusion lie in the myth that there was a fundamental philosophical difference between the American and French Revolutions. In fact, there was a shared Enlightenment project—deeply informed by Protestantism—running straight through the British revolutions of the 1600s, on through 1776, into 1789.

The “English Civil War” of the 1640s essentially birthed modern Western civilization, with the sidelined yet influential Puritan faction known as the Levellers giving us the prototype for the Bill of Rights. In America, Puritans are known as the builders of society; In England, they’re the people who cut the King’s head off and nearly tore it all down. Britain’s follow-up revolution of 1688 was relatively quick and bloodless because that King (James II, a Catholic) believed parliament would also chop his head off if he didn’t flee the country.

American descendants of the Puritans initially celebrated the French Revolution because it ended “popery” and absolutism. It was partly started by the Marquis de Lafayette, and embraced by Thomas Jefferson. For a time there was a school of New England evangelists that celebrated the execution of Louis XVI as God’s work:

The regicide also made sense to those who saw world events in apocalyptic terms. Ridgefield Baptist minister Elias Lee, for example, saw the regicide as wholly ‘justifiable.’ The ‘destruction of the royal family’ was ‘providential retaliation of the persecutions, murders, and massacres, of thousands and thousands of poor protestants.’ While there might have been too much zeal and haste on the part of the National Convention in reaching its verdict, the act itself was the fulfillment of numerous prophesies. Similar sentiments were expressed by Benjamin Farnham of Granby. While the king and the royal family fell victim to the frenzy of the mob and suffered ‘the most horrid cruelties,’ it seemed a fitting recompense for the thousands of Protestants killed by the ‘royal monsters,’ and ‘comport[ed]with the prophecy extremely well.’ To Richard Brothers, the English prophet, whose works were published in Connecticut, ‘the revolution in France and its consequences proceeded entirely from the judgment of God.’ (“Connecticut Confronts the Guillotine” by Robert Imholt, The New England Quarterly , September 2017)

Since Americans had already attained religious liberties secondhand through the English revolutions, they understood that they’d never have to fight a total war for them, but the French did. (Some of France’s most notorious policies, like the seizing of church estates, had been done in England even before the Enlightenment, during the Reformation reign of Henry VIII.)

Americans had also never been stalked by famine, as the French people were under Louis XVI. To be sure, some founding Americans were horrified by the Jacobins, but it seems most were not: In 1800 they elected Thomas Jefferson—widely identified with the Jacobins—to be president.

Under pretence of governing they have divided their nations into two classes, wolves & sheep…I can apply no milder term to the governments of Europe, and to the general prey of the rich on the poor.

- Thomas Jefferson writing from France under the reign of Louis XVI, 1787

Early Americans likely understood that the Reign of Terror was not a direct product of revolution, but a result of international war against France. The decision for that war was made by foreign aristocrats like the Duke of Brunswick who repeatedly threatened France’s sovereignty, even though Paris was still giving constitutional monarchy a chance as late as 1791. Long before the Terror began, Prussian troops were marching into the country, with a dozen other kingdoms preparing to join them.

The American Revolution was spared the desperation that leads to Terror precisely because it had the powerful French Empire as an ally in 1776. By the time of its own revolution, France herself had no allies. America’s refusal to join in the battle against the old aristocracies—after George Washington’s call to avoid “foreign entanglements”—facilitated the isolation that led to France’s anguish. These differences are circumstantial not philosophical, as evidenced by the fact that the great philosopher 1776, Thomas Paine, supported both revolutions with equal fervor.

Edmund Burke, First Neocon of the Modern World

Some populists today are enamored of Edmund Burke, British parliamentarian and sworn enemy of revolutionary France. While a stylish writer, Burke’s arguments and evidence against France nonetheless verged on the absurd (Paine demolished most of them in his book The Rights of Man). Burke accepted the British revolution of 1688 and the American Revolution, but considered the French Revolution a bridge too far because, he said, it turned fathers and sons violently against one another. Burke seems to have forgotten the fact, quite notorious in his time, that Benjamin Franklin had allowed his son William to be locked up in solitary confinement for nearly a year for supporting the British, an ordeal which nearly killed the younger Franklin. Benjamin never forgave his son or any other Loyalists, and like the rest of them William fled to exile. If the 75,000 Loyalists had not been invited into other colonies by George III, would their fate have been any different from Marie Antionette?

Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France might be the most elitist book in the Western canon. The most recent populist upset in the US came when a truck driver was elected to the New Jersey Senate; The original People’s Party featured miners and bricklayers as political candidates; But here is Edmund Burke’s policy on working-class governance:

The occupation of a hairdresser or of a working tallow-chandler cannot be a matter of honor to any person—to say nothing of a number of other more servile employments. Such descriptions of men ought not to suffer oppression from the state; but the state suffers oppression if such as they, either individually or collectively, are permitted to rule.

We’re a long way here from the MAGA credo of “I love the poorly educated.” What’s more, Burke doesn’t seem to believe that average people have a right to vote at all: “as to the share of power, authority, and direction which each individual ought to have in the management of the state, that I must deny to be amongst the direct original rights of man in civil society.”

In this supposedly classical liberal tome, Burke rejects the application of protected natural rights, which is a pillar of contemporary populist thought:

Society requires not only that the passions of individuals should be subjected, but that even in the mass and body, as well as in the individuals, the inclinations of men should frequently be thwarted, their will controlled, and their passions brought into subjection. This can only be done by a power out of themselves, and not, in the exercise of its function, subject to that will and to those passions which it is its office to bridle and subdue. In this sense the restraints on men, as well as their liberties, are to be reckoned among their rights. [emphasis added]

Anthony Fauci himself could not have articulated a better denunciation of the “ideological bullshit” of liberty and non-expert governance.

It’d be one thing if Burke declared his anti-democratic principles as an attempt to minimize violence, but Burke demonized revolutionary France as a rationale for expanding war. When peace negotiations were advancing between France and England in 1796, Burke wrote a book denouncing it and calling for renewed warfare to impose monarchy on Paris (even while most Tories promoted peace). The outcome of such attitudes was the Napoleonic Wars—the most deadly series of events in 19th century Europe. In other words, Edmund Burke was the first neocon of the modern world.

Some have defended Burke by saying that he decried absolutism, colonialism and slavery, but his fine words did nothing to stop those things—revolutionary action did. The frightful Jacobins were the first Europeans to abolish slavery, but Burke saw this as “mad democracy,” and seems to have supported the British battles to make Haitians into chattel again.

In an era of Woke capitalism and communist Chinese billionaires, the debate over what Marxism really means may go on for awhile. But to right-wing intelligentsia it seems to mean any time masses of people take revolutionary action against the elite to end their enslavement. Considering that Christopher Rufo’s homebase is the Manhattan Institute, a think tank funded by Bill Gates (along with the family that founded Blackstone group), it seems likely that counter-revolution, not revolution, is his agenda. Those seeking the spirit of Samuel Adams will have to look elsewhere.